The Science of Corals

This article is also available at Inspire EdVentures.

What Are Corals?

“Coral” can be used to describe thousands of individual species. Corals are animals - not plants, despite their sometimes plantlike appearance - of the phylum Cnidaria, which includes jellyfish and hydrozoans. Within Cnidaria, corals belong to the class Anthozoa, making them most closely related to anemones.

A colony of great star coral, Montastraea cavernosa. Image by Tobacco Caye Marine Station.

A single coral colony is made up of up to hundreds of thousands of individual animals, called polyps, which can be as small as a few millimeters across. A polyp is shaped like a hollow tube with one open end, through which food enters and waste is expelled, and one closed end, which allows the polyp to attach to the sea bed or to other polyps and form a coral colony.

Polyps may be small, but they have a hidden weapon. The open end of the polyp is surrounded by tentacles equipped with barbed, stinging cells called nematocysts, which are common across all animals of the phylum Cnidaria. These nematocysts can be used both to capture prey and to defend the coral polyp and colonies, including against other competing corals.

A polyp of Leptastrea purpurea, a species of stony coral. Image by Narissa Spies.

Classifying Corals

Classification of corals is, at best, complicated, and always under revision as new evolutionary relationships are discovered. Corals (class Anthozoa) may belong to one of two subclasses: Hexacorallia and Octocorallia. Hexacorallia includes stony corals (order Scleractinia) and black corals (order Antipatharia), and their relatives: sea anemones, corallimorphs, and zoanthids. Octocorallia contains the soft corals (order Alcyonacea) and the blue corals (order Helioporacea).

An overview of coral classification and some close relatives of the corals. Image by Inspire EdVentures.

Stony corals (Scleractinia) are also known as “true corals,” and are perhaps the most famous type of coral due to their relationship to coral reefs. Stony corals are named for their hard external skeleton made of calcium carbonate in the form of aragonite, which provides a rigid framework for the coral colony to build upon. (Calcium carbonate is the same material used by other organisms to make seashells.) Though other forms of coral are present on reefs, coral reefs themselves are made almost entirely of stony coral. Stony corals include well-known reef staples such as brain coral, star coral, and elkhorn coral.

Grooved brain coral, Diploria labyrinthiformis, is an example of stony coral. Image by Tobacco Caye Marine Station.

Soft corals (Alcyonacea) lack stony corals’ external skeletons. Instead, soft corals contain thin structures called sclerites - which are also made of calcium carbonate - that provide support for the corals’ tissues. Soft corals form colonies and may be found in or near reefs, but are not true reef-builders like stony corals. Gorgonian corals such as sea fans and sea whips, which were formerly classified as a separate order, are today considered part of order Alcyonacea.

A soft coral of the Dendronephthya genus, also known as carnation coral. Photo by Ahmed Abdul Rahman.

Black corals (Antipatharia), sometimes known as thorn corals, are more closely related to stony corals than to the “true” soft corals of order Alcyonacea. However, like soft corals but unlike stony corals, black corals do not have external skeletons. Black corals are most often deep-water species, with some being found at depths of nearly 20,000 feet (6,000 meters).

A species of black coral, Antipathes dendrochristos, also known as Christmas tree coral. Photo by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

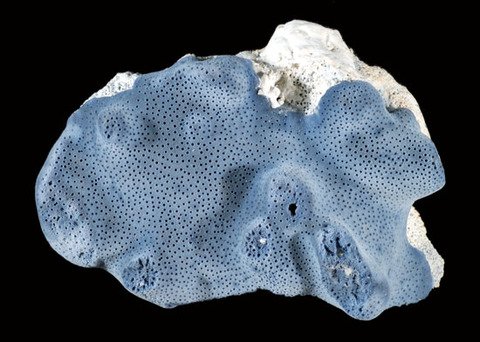

Blue corals (Helioporacea) are the odd corals of the bunch. Consisting of a single species, Heliopora coerulea, blue coral is found only on shallow-water reefs in the Indian Ocean, with large colonies that can reach up to 6.5 feet (2 meters) in diameter. Like stony corals, blue corals secrete hard skeletons of aragonite, and are in fact the only octocorals (members of the subclass Octocorallia) to have external skeletons.

A preserved specimen of Heliopora coerulea, showing its distinctive blue color. Image by the Yale Peabody Museum.

Also included in class Anthozoa are corallimorphs, zoanthids, and sea pens. Corallimorphs blur the line between coral and anemone, and are sometimes called mushroom corals or false corals. (Mushroom coral, which lives individually instead of forming colonies, have polyps up to 5 inches (12.7 cm) across.) Zoanthids are unique in forming structures of marine sediment, such as sand, to support the polyp or colony. Sea pens resemble plants or even feathers stuck into the sea bed, and are classified as octocorals.

A corallimorph from genus Discosoma. Image by user Haplochromis.

What Do Corals Eat?

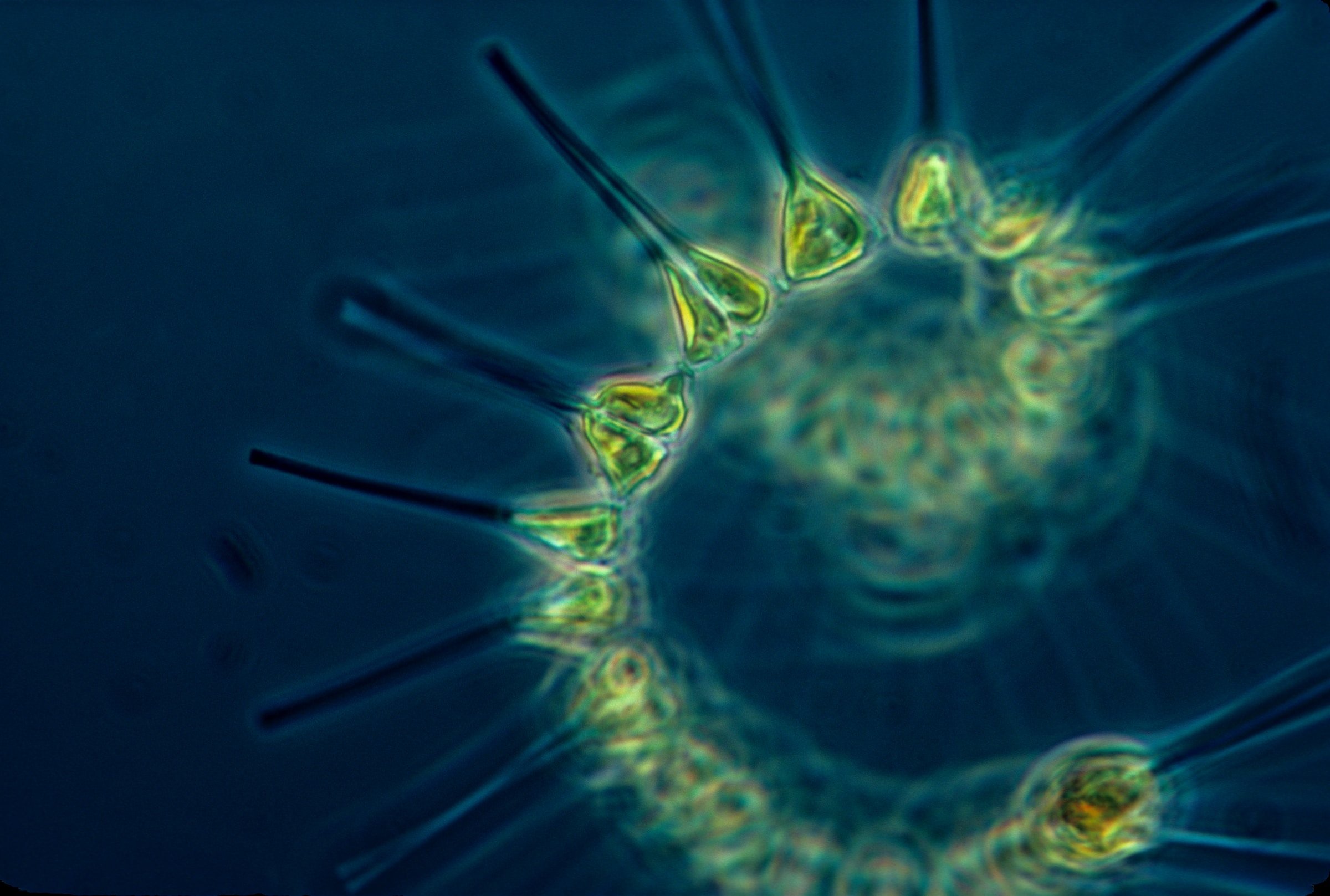

Corals are mainly filter feeders, meaning that instead of hunting their food, they use their tentacles to “filter” it from the ocean currents around them. This food includes very small organisms such as phytoplankton and zooplankton, some of which cannot be seen without a microscope.

Some corals - mainly those in warm, shallow waters - have a symbiotic relationship to zooxanthellae, a type of algae that lives in their tissues. Zooxanthellae are photosynthetic, meaning that they produce energy from sunlight, like terrestrial plants. Some of this energy is taken up by the coral host. Zooxanthellae can also be responsible for coral pigmentation, especially the green, brown and red colorations.

Coral bleaching events, which occur when ocean conditions become too hot or acidic for corals to thrive, involve a coral colony expelling zooxanthellae from their tissues. This causes the corals to appear white or translucent. Though the corals themselves are often not immediately killed, and may recover from small-scale bleaching events, the loss of zooxanthellae can lead to starvation in coral colonies over time.

An example of coral bleaching. Photo by Naja Bertolt Jensen on Unsplash.

How Do Corals Reproduce?

Corals engage in both sexual and asexual reproduction. Asexual reproduction takes two forms, budding or fragmentation, and produces offspring genetically identical to the parent. In budding, a coral polyp simply divides into two, expanding the coral colony. Fragmentation occurs when a piece of the coral colony is dislodged, such as by a storm or another sea organism. If the coral fragment reaches a suitable area, it may become rooted in the sea bed and eventually grow into a new coral colony.

Sexual reproduction in corals is often more complicated. Many corals can produce both eggs and sperm, which are released into the water column in spawning events. These spawning events are triggered by environmental conditions or even time of year and may occur on a massive scale. Once fertilized, the coral eggs mature into new, unique polyps, which may form their own colonies and begin the reproductive cycle once again.

Spawning elkhorn coral in the Florida Keys. Image by Brett Seymore at FWC Fish and Wildlife Research Institute.

Learn More About Coral Reefs!

In Part Two of this article we take a closer look at structure and importance of a coral reef, as well as threats to this important ecosystem.